Corporate foresight

Corporate foresight is an ability that includes any structural or cultural element that enables the company to detect discontinuous change early, interpret the consequences for the company, and formulate effective responses to ensure the long-term survival and success of the company.[1]

The motivation to develop the corporate foresight ability has two sources:

- the high mortality of companies that are faced by external change. For example a study by Arie de Geus of Royal Dutch Shell came to the result that the life expectancy of a Fortune 500 company is below 50 years, because most companies are unable to adapt their organization to changes in their environment.[2]

- the continuous need for companies to explore and develop new business fields, when their current business fields become unprofitable. For this reason companies need to develop specific abilities that allow them to identify new promising business fields and the ability to develop them.[3][4]

Corporate foresight to overcome three major challenges

There are three major challenges that make it so difficult for organizations to respond to external change:[1]

- a high rate of change that can be seen in (1) shortening of product lifecycles, (2) increased technological change, (3) increased speed of innovation, and (4) increased speed of the diffusion of innovations

- an inherent ignorance of large organizations that results from (1) a time frame that is too short for corporate strategic-planning cycles to produce a timely response, (2) corporate sensors that fail to detect changes in the periphery of the organizations, (3) an overflow of information that prevents top management to assess the potential impact, (4) the information does not reach the appropriate management level to decide on responses, and (5) information is systematically filtered by middle management that aims to protect their business unit.

- inertia which is a result from: (1) the complexity of internal structures, (2) the complexity of external structures, such as global supply and value chains, (3) a lack of willingness to cannibalize current business fields, and extensive focus on current technologies that lead to cognitive inertia that inhibits organizations to perceive emerging technological breakthroughs.

Need for corporate foresight

In addition to the need to overcome the barriers to future orientation a need to build corporate foresight abilities might also come from:

- a certain nature of the corporate strategy, for example aiming to be "agessively growth oriented"

- a high complexity of the environment

- a particularly volatile environment

To operationalize the need for "peripheral vision", a concept closely linked to corporate foresight George S. Day and Paul J. H. Schoemaker propose 24 questions.[5]

[edit] The five dimensions of the corporate foresight ability

Based on case study research in 20 multinational companies René Rohrbeck proposes a "Maturity Model for the Future Orientation of a Firm". Its five dimensions are:

- information usage describes the information which is collected

- method sophistication describes methods used to interpret the information

- people & networks describes characteristics of individual employees and networks used by the organization to acquire and disseminate information on change

- organization describes how information is gathered, interpreted and used in the organization

- culture describes the extent to which the corporate culture is supportive to the organizational future orientation

To operationalize his model Rohrbeck used 20 elements which have four maturity levels each. These maturity levels are defined and described qualitatively, i.e. by short descriptions that are either true or not true for a given organization.[1]

Read

http://futureorientation.net/2010/07/29/what-is-organizational-future-orientation/ Please read all 5 Responses to What is Organizational Future Orientation (visit each and every response).

What is Organizational Future Orientation

As our first blog entry I would like to introduce Organizational Future Orientation. We define OFO as:

Organizational future orientation (OFO) is the ability to identify and interpret changes in the environment and trigger adequate responses to ensure long-term survival and success.

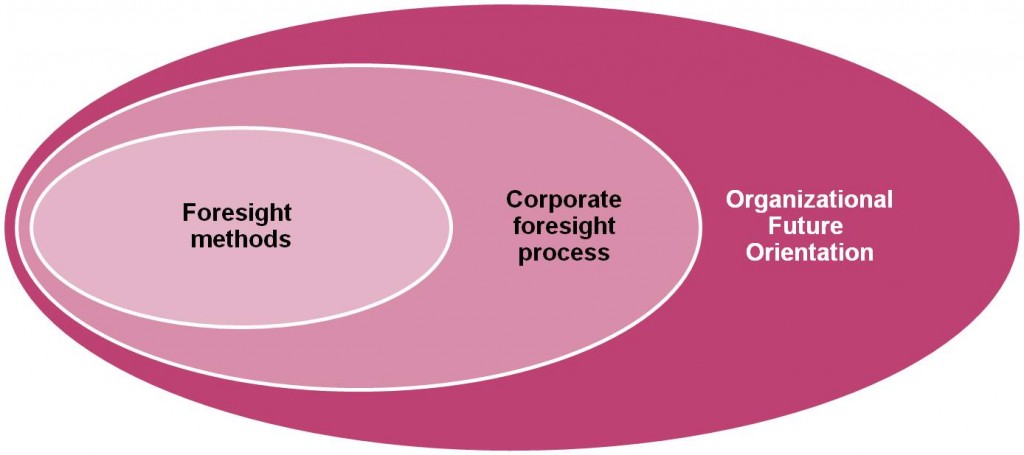

To tackle the questions how companies become future oriented and thus ensure long-term survival and success, scholars have worked on different levels (see figure below). Some have done research on

- foresight methods such as scenario technique, delphi analysis, etc., that allow us to explore the future, identify alternative futures or make predictions and

- others have worked on corporate foresight as a process. These scholars imply that there is a corporate foresight function, possibly also a corporate foresight unit that generates insights into the future and channels these to other corporate functions such as innovation management, strategic management, corporate development, marketing, or controlling.

- When we talk about organizational future orientation we appreciate that this ability can be build upon a corporate foresight unit, that utilizes foresight methods, but we also include the possibility that a firm builds its future orientation upon other means, such as encouraging all employees to look for external change and empowering them to respond to this change with individual initiative, possibly through corporate venturing schemes.

Are winning companies building future orientation on people or process?

As discussed in our first blog post, we believe that future orientation can be attained both by

- foresight and strategic management processes and by defining responses top-down and

- by encouraging all employees to be on the lookout for external change and empower them to take personal initiative to drive change.

In our last blog post we reported on a case study where we a company had a long track record of successfully reinventing itself repeatedly, thus displaying clearly a high future orientation. But this company has very limited corporate foresight capabilities.

In our new poll we would like your opinion on what is the stronger mechanism to build future orientation: (1) structured process or (2) empowered people.

We are looking forward to your view and if you have example we would love to hear about them. Please share them by leaving a comment to this post.

Organizational Future Orientation at the Academy of Management

This years Academy of Management Annual Meeting in Montreal has attracted over 9000 scholars from around the world. Given the size of the conference there were multiple tracks that touched Organizational Future Orientation.

My paper was discussed in the Organizational Development and Change (ODC) track. For presentation of the findings within the round table presentation I was asked to provide a handout which you can download here. It gives a brief overview of our research and shows our Maturity Model on Organizational Future Orientation and the barriers and process model how weak signals are translated in managerial action.

I also want to express my gratitude to the ODC division for honoring our research with the Rupe Chisholm Best Theory to Practice Paper Award.

Theoretical foundation: Dynamic Capabilities

The dynamic-capabilities theory has been introduced by David J. Teece as an extension of the resource-based view of the theory of the firm. The resource-based view proposes that the ability of a firm to create and maintain a competitive advantage is based on a certain set of strategically relevant resources, which are (1) valuable, (2) rare, (3) difficult (if not impossible) to imitate and (4) non substitutable. Teece observed that in changing environmental conditions, like for example a technological disruption, companies will have to adapt their portfolio of resources.

Take the example of Kodak which was clearly the dominant firm in the imaging market when the market was still based on chemical processes rather than digital image processing. With the change to digital photography Kodak was still well equipped with the needed resources to create a competitive advantage when competing on selling film or processing the printing of images on paper. In the digital world however different resources were needed to provide the customer with a superior imaging experience.

Technologically wise there was the need to develop sensors to translate an image into a digital signal, write software that allows treating digital images and create digital photo albums so that customers can store, share and show their images.

Most likely the needed resources for the digital world would also have included managerial abilities such as forming and managing alliances with partners that can contribute complementary assets, such as software companies or companies that can play complementary roles in the new value chain.

Teece proposes that companies that are in a situation similar to Kodak’s need to have the:

(non-imitable) capacity [...] to shape, reshape, configure, and reconfigure assets (resources) so as to respond to changing technologies and markets[...]

In our view of organizational future orientation we agree with this assumption and add a particular emphasis on the role of the manager to enable and sustain the dynamic capabilities of a firm. As we pointed out in our post on technology scouting the success can only be assured if individuals drive the process that combines intelligence gathering and acting (for example acquiring the needed technologies).

Likewise we do not believe that the process steps of dynamic capabilities proposed by Helfat et al. (2007): (1) search & selection, (2) decision making, (3) configuration & deployment, and (4) implementation can be judged or managed independently, but rather propose that they have to be driven by committed and capable individuals along the whole process.

We therefore propose that for advancing the future orientation of a firm we have to study closer the role of the manager – a view also advocated by strategy-as-practice scholars – who should be able to:

- identify external environmental change

- integrate and interpret different perspectives

- recognize the need to reconfigure the portfolio of strategic resources of the firm

- take action, orchestrate and drive the renewal of the resource portfolio

For further reading we have assembled a collection of relevant literature in our reader for underlying theories in our bibliography (click here to go to dynamic capabilities literature).

For further reading we also recommend an Interview with Jeffrey Martin, author of the highly cited article: “Dynamic Capabilities: What are they?”Theoretical foundation: Strategy as Practice

In our last post on theoretical foundations we described dynamic capabilities. While the dynamic capability perspective can be regarded as the main-stream view in strategic management research, we want to present today an emerging stream: strategy as practice.

The dynamic-capabilities perspective deals with resources and capabilities that organizations have. The strategy-as-practice perspective deals with what actors within organizations do, it deals with rationality, action, interaction and habituation. Strategy as practice is also more open about the outcome. While the traditional strategic management research is ultimately always after organizational performance the strategy-as-practice view recognizes also other achievements such as creation of common goals or change of mental models as outcomes in their own right.

We therefore think that strategy-as-practice view could be more appropriate for research on organizational future orientation and also produce insights that are more actionable and that have higher practical relevance.

For further reading we have extended our reader of underlying theories with a section on conceptural and empirical work with a strategy-as-practice perspective.

Strategic Issue Management – an ability of Organizational Future Orientation

Ansoff introduced the concept of “Strategic Issue Management” in 1980. A strategic issue is “…a forthcoming development, either inside or outside of the organization, which is likely to have an important impact on the ability of the enterprise to meet its objectives.” (Ansoff, 1980). As he adds, an issue can be an emerging opportunity in the organization’s environment or an internal strength, as well as an external threat or an internal weakness, respectively.

A Strategic Issue Management system is described as “…a systematic procedure for early identification and fast response to important trends and events both inside and outside an enterprise” (Liebl, 2003)

Liebl (2003) identifies four functions of a Strategic Issue Management system:

- Early detection of trends and issues in the environment

- Understanding the discontinuities which are imminent because of the trends and issues

- Assessment of the resulting strategic implications

- Taking measures

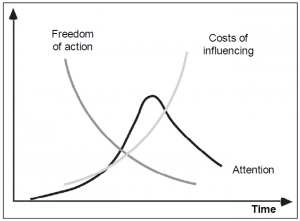

While Environmental Scanning primarily deals with the identification of issues, the concept of Strategic Issues Management puts more emphasis on monitoring issues and reacting to them. The issue life cycle was introduced by Downs as a model for the development of an issue throughout time (Downs, 1972). A common visualization of the issue life cycle is shown in the figure below, which characterizes the issue from its emergence until its disappearance.

Figure 1: Issue Life Cycle (Liebl, 2000)

Figure 1: Issue Life Cycle (Liebl, 2000)

It is shown that the opportunity for an organization to react upon an issue (freedom of action) decreases throughout time in several aspects:

- time pressure for effective communication or strategic realignment increases.

- the range of possible activities for influencing the events at hand – a legislative procedure, for instance – decreases.

At the same time, the organization’s costs of responding increases over time (Liebl, 2000) In addition a interest curve can be defined that reflects public interest in an issue. The rapid increase of the curve is due to the fast dessimination of information and opinion through the various media channels. The public attention than puts pressure on policy makers to take actions such as launching legislative initiatives. However the attention also decreases rather fast as public interest is difficult to maintain for long over time (Liebl, 2003)

For Organizational Future Orientation we hypothesis that issue management inside an organization follows a similar sequence. That could mean that corporate foresight activities would help to detect the emergence of an issue early. But at the same time corporate foresight needs also to interprete the impact of the issue and propose an adequate response to it while the attention of internal stakeholders is still high. If the attention is already starting to drop the risk is that no action will be taken.

This blog article builds on the master thesis of Sebastian Knab.

Re-visit your questions that followed reading the Masi Center Learning Perspectives- part 1 and part 2 in unit 3 (full document was attached). You studied the strategic learning approaches described throughout the two chapters of the Masi book and now is the time to assess how can answering the questions you posed help you in achieving a corporate insight. One example of such a question that you could copy from the text was: What problem were we trying to solve? An example of a question that you might have wanted to pose was: What were we trying to avoid? What other questions did you ask? What are your responses now?

Re- visit http://www.forbes.com/2010/04/20/global-2000-leading-world-business-global-2000-10-intro_2.html and choose one company (Mac Donalds, for instance) and list at least three corporate foresights based on Forbes analysis (provided or at least eluded to in the text).

Special Report

The World's Leading Companies

Scott DeCarlo, 04.21.10, 06:00 PM EDTThis comprehensive report analyzes the world's biggest companies and the best-performing of these titans.

The Forbes Global 2000 are the biggest, most powerful listed companies in the world. These global giants usually reorder themselves at a glacial pace, but sometimes--as with the volatile financial sector of late--with more abruptness.Extreme vagaries of business or poor performance can take them off the list entirely. In any case, our composite ranking is the best snapshot of just how these titans compare. As we show, the corporate dominance of the developed nations is steadily receding. With respect not just to size but to what investors care most about, see our Global High Performers, an elite list of companies that set the pace in their respective industries.

Video: The Biggest Names In Business

Forbes' ranking of the world's biggest companies departs from lopsided lists based on a single metric, like sales. Instead we use an equal weighting of sales, profits, assets and market value to rank companies according to size. This year's list reveals the dynamism of global business. The rankings span 62 countries, with the U.S. (515 members) and Japan (210 members) still dominating the list, but with a combined 33 fewer entries.

Interactive World Map: An Atlas Of The World's Biggest Companies

This year, the following countries gained the most ground: mainland China (113 members), India (56 members) and Canada (62 members). Even Oman and Lebanon are now Global 2000 members. Also gaining a significant presence on our list this year are corporations from Ireland, South Africa and Sweden.

In total the Global 2000 companies now account for $30 trillion in revenues, $1.4 trillion in profits, $124 trillion in assets and $31 trillion in market value. All metrics are down from last year, except for market value, which rose 61%.

Related Story: The World's Leading Companies, By The Numbers

An analysis of the Global 2000 shows that despite the turmoil in the financial sector, banks still dominate, with 308 companies in the 2000 lineup, thanks in large measure to their asset totals. The oil and gas industry, with 115 companies, scores high in sales, profits and stock-market value, yet these sectors were not the leaders in growth over the past year. Insurance companies (up 27%) led all sectors in sales growth, while the leaders in profit growth were drugs and biotech firms (up 20%).

Our full list is rich with industry leaders who are making strategic moves to help navigate through these tough economic times. Among them you will find Taiwan's Acer, aiming to become the biggest seller of laptops and netbooks by 2011, and Danish biotech Novozymes, finding new uses for enzymes.

For the past few years we have also identified an important subset of the Global 2000: big companies that also have exceptional growth rates. To qualify as a Global High Performer, a company must stand out from its industry peers in growth, return to investors and future prospects. Most of the 130 Global High Performers have been expanding their earnings at 28% a year and 20% annualized gains to shareholders over the past five years.

Both Acer and Novozymes are on our Global High Performers list, and 77 of the 130 companies on this select list have headquarters outside the U.S. Our list includes global brand names, such as Belgium's Anheuser-Busch Inbev ( BUD - news - people ), H&M ( HNNMY - news - people ) (Sweden) and Honda Motor ( HMC - news - people )(Japan), as well as foreign companies with lower profiles, such as Australian drug company CSL ( CMXHF.PK - news - people ).

Among notable U.S. Global High Performers are Apple ( AAPL - news - people ), Google ( GOOG - news - people ), McDonald's ( MCD - news - people ) and Nike ( NKE - news - people ).

To find these global superstars, we analyzed 26 industries of the Global 2000 (we excluded trading companies) and gave each company respective scores for long-term and short-term sales and profit growth; return on capital; debt-to-capital (the lower the better); and total return over five years. Other requirements for the global high performers list: shares traded in the U.S. or Depositary Receipts, positive equity and sales of at least $1 billion.

No comments:

Post a Comment